Do dictators care about climate change?

The complicated influence of democracy and autocracy on national climate action

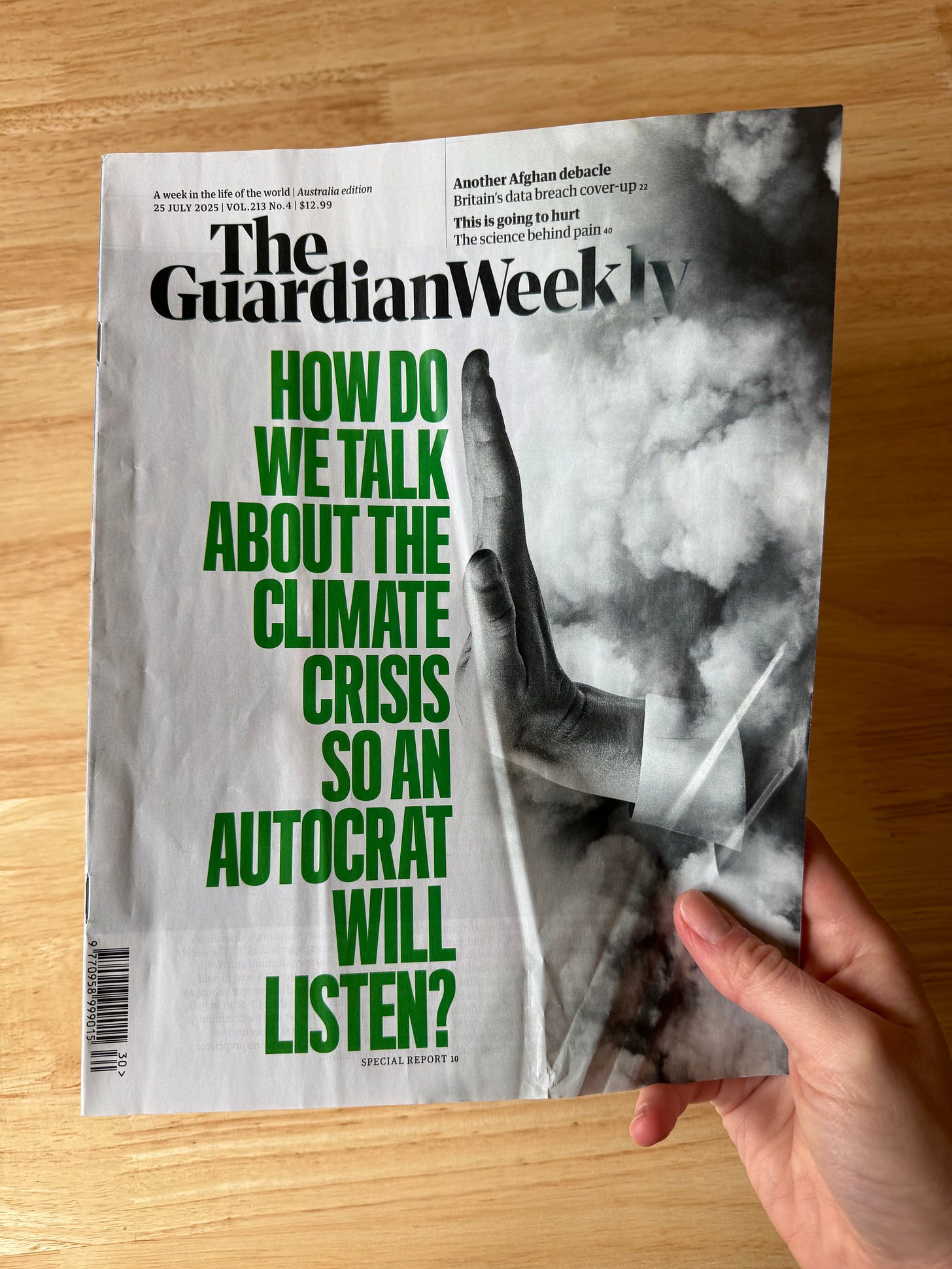

Last week, The Guardian published a ‘report’ titled How do we talk about the climate crisis so an autocrat will listen?

Interesting — I bought it.

In climate circles, the conclusion of countless essays and podcasts and protests is that we, the people, must put pressure on our governments to solve this global crisis. That might stand a chance in Norway, or Australia, or Taiwan, but just 6% of the world lives in a ‘fully functioning’ democracy. That’s a dramatic figure (it includes countries like France and the US in its ‘flawed democracies’). But flawed and ‘hybrid’ regimes aside, more than a third of countries are full-blown authoritarian states. In these countries, no amount of people pressure is likely to sway the man (and they are all men) at the helm.

Autocrats, like the rest of us, are really just looking out for their own interests. Talking to Putin about climate change is not unlike talking to my grandpa about why he should divest from fossil fuels. The returns have been great so far. Why would either of them stop? (My grandfather is a wonderful person and not a Russian dictator.)

And really, it’s no different from every other climate conversation we need to have. Whether it’s aimed at corporations, governments, or individuals, it always boils down to: how do we get people to act in the collective interest when it appears to run counter to their personal interest?

I was curious to see what the article would say about that. Unfortunately, it didn’t say much.

Who takes more climate action: democracies or autocracies?

If you’re up to date on climate news then you were probably wondering this from the beginning: who says democracies have the high ground here? Fair question.

The research is mixed, but there is no slam-dunk trend showing that democracy leads to better climate or environmental outcomes. (National wealth does — eventually — but there are plenty of wealthy autocracies.)

Climate action is highly dependent on whoever is in power, and one strength and flaw of democracies is that power tends to change hands on a regular schedule. At the same time, while autocracies are dominated by a strongman, their party, and a toxic sprinkling of wealthy insiders, democracies don’t always rise far above this. Most of the world’s democracies are still unduly influenced by big business interests. And climate action has appeared to be at odds with big business interests for decades.

So one of the benefits of autocracies (and I use the term benefits loosely here) is their timescales. U.S. policy runs on four-year timelines (for now). What can we get done in four years to get people to vote for us again? Same goes for most democracies. In Australia, we’re on a three-year loop. Autocrats don’t have to worry about pesky elections interfering with their plans, which means they can plan on far longer time horizons.

Take Russia interfering in US elections, part of its (very) long-term play to destabilize Western democracy. Or China’s big-picture strategy to knock the US off its podium and replace it as the global superpower.

Another ‘benefit’ of autocracies is how coordinated they can be in their national responses to emergencies or other state goals. If the state wants to move, it can move anything and everything. That’s a terrifying prospect generally, but potentially powerful when applied to something like climate action.

A long-term vision, policy consistency, public-private coordination, and a willingness to act without immediate payoff are all essential for meaningful climate action. And that’s why, in theory, autocracies could be fertile ground for climate leadership. But only under one condition: the leaders must believe that climate action uniquely benefits them, and isn’t simply a contribution to a global problem.

I think the real question is not how to get autocracies to listen to our arguments. It’s how do we get them to start making their own arguments — forming their own conclusions — that this makes strategic sense for them.

How do we lead autocracies to the conclusion that climate action is in their own interest?

Here’s one area where I think the Guardian article misses the mark — and it’s a common misunderstanding in climate discourse: conflating individual mitigation efforts with adaptation or climate protection. The piece quotes Christiana Figueres, former UN climate chief, saying, “While states drag their heels on their Paris agreement commitments, state-owned companies are dominating global emissions – ignoring the desperate needs of their citizens.”

But Figueres is implying that any country facing climate impacts would serve its citizens best by cutting its emissions. That’s not really true.

In the short term, what actually helps people on the ground is adaptation: infrastructure, preparedness, resilience. In the long term, what will help future generations is coordinated global mitigation. A single country reducing its emissions may be the morally right move, but it won’t meaningfully protect its own citizens from the spiky end of climate change. Not on its own. The only thing it will do is make the country less vulnerable to accusations of hypocrisy.

That’s actually important for democracies, where hypocrisy can damage global relationships. (When it comes to climate action, democracies have proven themselves the ultimate hypocrites.) Autocrats, on the other hand, tend not to worry too much about being seen as hypocrites.

So I don’t think we’ll make much headway telling autocracies to reduce their emissions in order to help their citizens affected by climate change. In the first place, that’s not how climate action works, and in the second place — well — most dictators simply won’t care if some of their countrymen lose their homes to wildfires or their crops to drought.

They’re not relying on their votes, anyway.

So — could we sanction them? Cut them off?

The Guardian’s main practical suggestions for persuading dictators to take climate action involves punitive economic measures, like the EU’s CBAM. The problem, as the authors note, is the lack of precision. CBAM may punish Saudi oil exports, but it hurts African aluminium in the process — and so on and so on. There are ways to lessen the negative side effects, but ultimately, most pricing mechanisms lead to the small guys getting hit harder than the big guys, regardless of their governance structure.

And that doesn’t mean these tools aren’t worth pursuing, but even when widely applied, they might make a small dent in an autocracy’s emissions, but are unlikely to get them truly on track.

For that, I think we’ll need more than sticks. For that, I think we’ll need carrots.

Take China, an autocracy that has taken a big bite out of the climate carrot.

Global superpowerdom is China’s ultimate goal, and one of its big bets on getting there relies on the country becoming a renewable energy / transition superpower. So far, it’s working. China’s emissions are falling (albeit slowly), and clean energy sectors accounted for 26% of the country’s GDP growth last year alone. It is the #1 producer of solar panels, electric vehicles, and batteries globally, by a long shot. A recent Ezra Klein podcast described China as the first global electrostate. (Yes, it is still the world’s biggest emitter — but that’s changing.)

China didn’t make this pivot because the democracies asked it nicely to reduce its emissions, or put CBAM between the country’s steel and its EU customers. It made the pivot because it looked 50, 75, 100 years into the future and said: this is our chance.

The only thing we need to say to autocrats is: there’s a way you can get rich from this.

But is the get rich argument only enticing to autocracies? Hardly. Sure, autocracies (particularly the older and more stable ones) might be more interested in regional and global domination, and they may very well be more willing to put up with the long-term horizons required for some climate investments to pay off. But superpowerdom is basically the same message we should be sending democracies too — particularly those ice-cold economists who see climate action as a cost and not as an opportunity. Every country wants a better economy. Every country wants global admiration.

Economic messaging is the key to climate comms in virtually all its forms — at the individual, corporate, and state level. Time to start talking business.

What we’re curious about this week

📚 Book: Original Sin, by Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson — a lot of people are very angry about this book, and I can see why. The timing of its release, combined with its hyperbolic title and cover would seem to make Tapper and Thompson into the ultimate opportunists. I agree with this criticism. The authors are no doubt sensationalists, and the tone throughout most of the book is overcooked. But I still think this is an important read, because it gets at one of the Left’s biggest problems: that in trying to save the world from one threat (Trump, in this case), we can fail to notice the risk right in front of us (a President no longer fit for the job). I recommend the audio version of this book — Tapper is an engaging and at times darkly funny narrator.

🇦🇺📚 Bonus book for the ~2 Aussies subscribed to this newsletter: The Great Divide, by Alan Kohler. A must-read for truly understanding our uniquely Australian-flavoured housing crisis.

🎙️ Podcast: Is Decarbonization Dead? — I was excited to see a climate-themed episode from my favourite NYT podcaster, and this one didn’t disappoint. Some great insights here into the insane lack of energy market logic behind parts of the Big Beautiful Bill (much of which makes no economic sense, climate aside). Quote I’m thinking about: “The next wave of energy politics will be about affordability.”

What we’re working on

👉 Wrapping up an ESG report: We’re putting the finishing touches on the first ESG report for a software company we’ve worked with previously. After this, we’ll transition into Phase 2 of our arrangement: helping them develop their ESG targets and strategy.

Ways we can help 🫶

🎯 Need help building an organic lead-generating machine? → See our lead gen services

📥 Want to know what’s trending in the world of sustainability reporting? → Download our free PDF: 2025 State of Sustainability Reporting

📣 Share this with your climate tech marketing team