Greenwashing and the tragedy of the commons

Why greenwashing matters at the macro level

I think we’re talking about greenwashing all wrong.

When we talk about greenwashing, we talk about consumers being misled or a brand damaging its reputation. The conversation revolves around individual harm: one company, one group of buyers, one product.

What we rarely discuss is the macro effect. What happens when false environmental claims become so widespread that they reshape the entire landscape?

In the early days, most sustainability claims were made by earnest early adopters and taken at face value. Then everyone else arrived. The mass embrace of ESG started to raise eyebrows, especially once it became clear that many of these claims were either entirely false or simply distractions from other, deeper violations.

We’re now living in the fallout of that shift — the post-greenwashing world, if you will. What started as an attempt to talk about real climate action ended up going something like this:

→ I buy this brand because it’s more sustainable.

→ Huh, that brand was lying? I’ll avoid that brand.

→ Wait, this brand was lying too? Okay, add that to the list…

→ Another one? And another one? You know what, I think I’ll just… stop believing any of it.

This breakdown leads to terrible outcomes for companies that are genuinely committed to sustainability (all three of them, globally). Green products and companies lose the edge they once had, and consumers stop believing any claims made by marketers.

And you know, maybe that’s not the worst thing. We could all use a reality check and a better understanding of market incentives. But I don’t think anyone wants to live in a world where nothing feels true, where every claim is suspect, and where cynicism becomes the default. Unfortunately, that’s where we’ve ended up, and the problem goes well beyond greenwashing.

We’re now in a post-greenwashing society. Not because brands suddenly decided to get honest, but because no one believes the claims anymore. That’s the real tragedy of greenwashing, and it’s one we rarely talk about.

Greenwashing and the tragedy of the commons

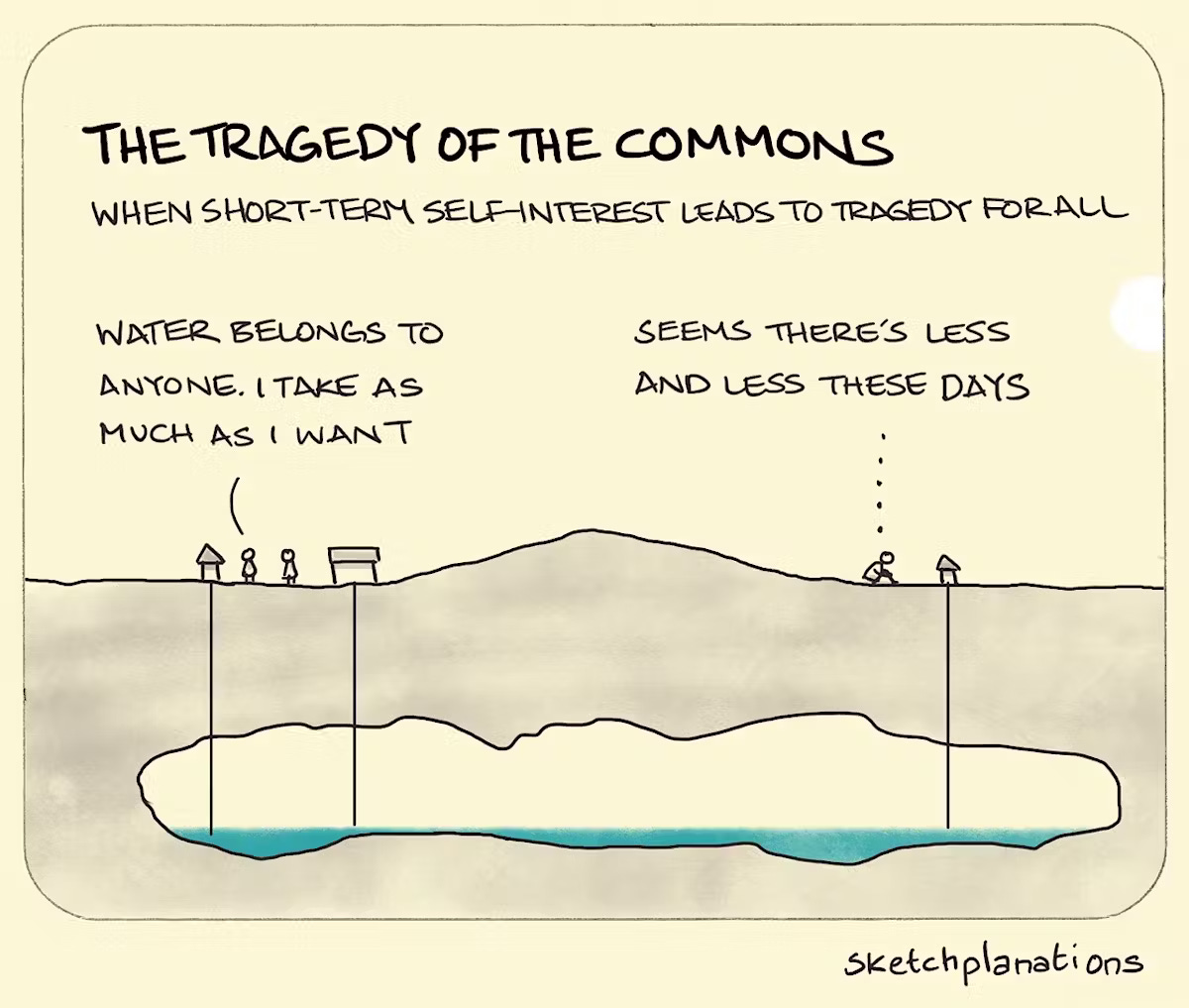

If you’ve spent any time in environmental circles, you’re familiar with the tragedy of the commons. This is the idea that when a resource is collectively owned — say, a river full of fish or an atmosphere free of pollutants — it will inevitably collapse from overuse.

Why? Because what benefits the individual (catching as many fish as possible) conflicts with what benefits the group (maintaining fish populations so they don’t collapse). And when we can’t trust others to act in the collective interest, there is no incentive for us to do so either. Why let them catch all the fish? We might as well cast our line.

There is no hero or villain in the tragedy of the commons. That’s what makes it a tragedy. Everyone is to blame, and in the end, everyone loses.

Most conversations about greenwashing focus on the brands (the bad guys) manipulating the consumers (the good guys). But greenwashing is not a story of oppressive power or manipulation; it’s just the tragedy of the commons at work in the free market. The commons here are not rivers or fish stocks, but something far more fragile: trust.

Every misleading claim depletes common trust, no matter who makes it. And unlike natural resources, trust seems to evaporate much faster and less rationally. Once it’s broken, it is very difficult to repair.

Yes, brands hurt consumers through greenwashing, but ultimately they hurt themselves and hurt the market. If companies can’t credibly communicate their climate action, they lose the very incentive to take it, because, like it or not, marketing and brand reputation are the primary drivers of voluntary climate action. If the market stops believing or caring about sustainability claims, that lever is gone.

I think that’s where we are today.

Life in a post-trust society

Greenwashing isn’t the only example of corporations trying to get something for nothing. It’s not the only reason big companies are under suspicion, and it’s not the sole cause of our growing disillusionment with the institutions that shape our lives.

Instead, it is just another accelerant speeding us toward a complete breakdown of trust — in markets, in institutions, in each other.

People talk about living in a post-truth society. But more than anything, we’re living in a post-trust society. Even when the truth is out there, we can no longer trust it when we see it.

That’s the crux of it. Assuming a company does not have monopoly control on a market (another issue for another day), then trust is the only thing keeping them in business. Take away trust and you have no market.

I’m all for a healthy dose of skepticism. People need to start paying less attention to what people and brands say and more attention to the incentives driving them. But while skepticism is necessary, I believe cynicism is dangerous, and nihilism (the last point on the spectrum) is existential.

I think we’re well past skepticism and deep into cynicism. I hope, for the good of humanity, we don’t reach nihilism.

What we’re curious about this week

📚 Book: No More Tears: The Dark Secrets of Johnson & Johnson, by Gardiner Harris

Speaking of corporate trust, if you want something to get mad about this week, I cannot recommend this book enough. I was skeptical that there would be enough wrong with J&J to fill a 14h+ book, but wow, was this a journey. Incredibly well written and reported, and an absolute must-read for anyone who still thinks this seemingly wholesome American company can’t be “that bad.” I listened to the audiobook; Harris has a great voice and is a passionate and compelling narrator.

🎙️ Podcast: Erin Ryan: The Murder of Charlie Kirk (The Bulwark Podcast)

When big, confusing things happen, I try to avoid social media and instead wait a few weeks or month for more nuanced takes to come out from people I trust. I couldn’t do that this week because the Charlie Kirk murder made me absolutely sick to my stomach, and I couldn’t think about anything else. I still avoided social media, but I turned to the podcasts instead — the closest thing I could get to a conversation. I found a few good ones, but this one was my favourite. A measured view of Charlie Kirk’s dark contribution to the conversations of today, but also a realistic and terrifying assessment of what this moment means for the MAGA movement and the far right generally.

What we’re working on

👉 SEO push: Many of our clients have seen the same rapid dropoff in traffic that is affecting most websites this year thanks to AI search overviews. We’re working alongside an SEO agency to help one of our clients combat this drop, producing a high volume of AI-friendly content to keep traffic up.

Ways we can help 🫶

🎯 Need help building an organic lead-generating machine? → See our lead gen services

📥 Want to know what’s trending in the world of sustainability reporting? → Download our free PDF: 2025 State of Sustainability Reporting

📣 Share this with your climate tech marketing team

It's really very important that if we're going to invoke the tragedy of the commons, we also say loudly that it's a myth. Elinor Ostrom deconstructed Hardin's seminal paper pretty thoroughly (and won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her efforts). It's been a few years since I read her work, but the key point that stuck is that Hardin fundamentally misrepresented the English commons as a laissez-faire open-access regime in which people were incapable of squaring short-term self interest with long-term maintenance. Ostrom's research showed empirically how commons regimes around the globe were (and are) much more sophisticated, with conflict resolution systems and robust self-governing mechanisms that overwhelmingly prevent exactly the sort of runaway misuse Hardin theorized. Contrary to the familiar saw, commons in and of themselves are not tragic, and in that I find good reason to resist nihilism.

Your bigger point is well-taken, though. Hardin's framework stands up in systems lacking cooperation, accountability, and guardrails, and as you argue, these are the conditions created when the common resource of trust is depleted. Scale is probably at issue here too; it's easier to maintain trust within smaller units than with some dispassionate global conglomerate headed by a sociopathic Lex Luthor wannabe. (How sad that that doesn't narrow it down to one person.) And as fragile as trust is, it's also remarkably fungible and, in the right conditions, self-perpetuating. Maybe replenishing the common supply has something to do with creating those conditions—the revolution will be local.