TCC #40: The ethics of ESG

Is 'risk management' the real risk?

Like most people, I got into this space to do good.

And then like a lot of people, I quickly realised I had to shed that frame and start talking about risk, and compliance, and strategic opportunity.

And now, like a handful of people, I'm going back to where I started.

I’ll rewind the clock to an SME interview I conducted on this very day last year. The woman I interviewed was an expert in supply chain risk management. I was looking for her insights on why supply chain ESG risk management matters, which in corporate terms translates to why senior executives should care.

We covered some familiar ground: reputational risk. Financial risk. Operational risk. Security risk. A whole lot of risk.

And then she pivoted.

“I also want to talk about the ethics of ESG,” she said. “We should be managing ESG risk because it’s the right thing to do.”

I’m surprised to say that I was surprised to hear this.

I talk about ESG and corporate sustainability all day, with scores of people — and rarely does the conversation get back to something as fundamental as “we should do it because it’s what’s right.”

Yet isn’t that what we’re all here to do?

Upon reflection, it’s pretty obvious how we got here.

In the 60s and 70s, climate activism was seen as intensely anti-business. You were either a ‘tree-hugger’ or a capitalist, and that was it.

Fast forward a few painstaking decades and we have the Kyoto Protocol in 1992. We have the now largely ridiculed COPs starting up in 1995. We have An Inconvenient Truth in 2006. We eventually get to Paris in 2015, and although it takes a few years, it really does start to ramp up global climate action. We have Greta skipping school on Fridays and a whole generation of kids coming to the dinner table and forcing their parents to reckon with their worldviews.

The world starts to accept that human-induced climate change is real.

But somehow it still feels like someone else’s problem.

In fact, positioning the climate crisis as someone else’s problem has basically been the playbook of fossil fuel marketing and PR teams since the turn of the century. You had Exxon hiding its very clear climate science, BP creating the ‘personal carbon footprint’, and a whole host of companies totally ignoring scope 3 emissions, as if supply chains are somehow dispensable to a company’s business model (more on that in another edition).

From the 2010s onward, we see less outright climate denialism from corporates and more of what Seth Klein calls ‘new climate denialism,’ where companies and politicians acknowledge the crisis, claim to care about it, purport to be acting on it — and yet carry on as before.

It may no longer be fashionable to deny climate change, but the tactics were now focused on deflection and obfuscation. Hiding ‘business-as-usual’ under weasel words like ‘carbon-neutral’ or ‘meeting consumer demand’ or ‘committed to a better future.’

Of course, even in the early days we had a few corporate vanguards that really took it to heart. Patagonia went all in. Ben & Jerry’s became a poster child. Tesla became Tesla (and then, you know — moved to Texas). But for the most part, most companies turn a blind eye. You were either a ‘green brand’ or a ‘normal brand’, to the exclusion of all nuance.

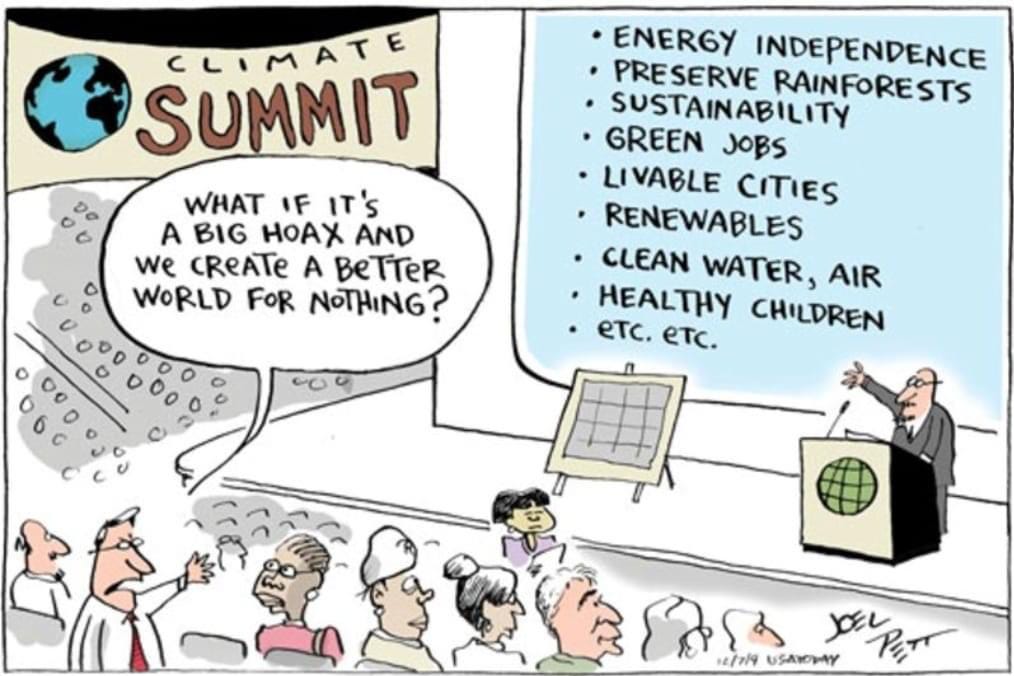

But then the climate movement made a rare and effective step.

It changed its messaging, deciding to couch the climate crisis in terms the suits could not only understand, but care about. The theory was that if you could frame corporate sustainability in business terms, it would be easier to get people on board.

So the climate crisis became physical risk. The climate movement became transition risk. Children buried alive in cobalt mines became social risk. Warlords and politicians profiting from deeply unethical arrangements with commodity traders and fossil fuel companies became governance risk.

Ad-actual-nauseum.

Where once we had corporate social responsibility (CSR), a department largely ignored by the ‘serious’ departments, much like billionaires and presidents handing the ‘charity stuff’ to their wives, companies started to treat sustainability as ‘serious business’. We’re now putting internal prices on carbon, asking for the ROI of our efficiency upgrades, and bringing the marketing team on board to turn sustainability into a ‘competitive advantage’ (more on that oxymoron in a future edition).

Unusually for the climate movement, it worked.

There's growing consensus that ESG is important for a company's bottom line — even if not next quarter or next year. There’s so much data to back this up that there’s almost no point me listing it here. Just Google “is ESG important?” and you’ll see that most of the important people in suits really do think (or at least claim to think) that it matters.

But why does it matter? In all this newfound consensus, I think we’ve lost something critical. In fact, I see two key problems with our new approach to corporate sustainability.

The first is that it’s often not all that compelling. You can give all the data about consumer preferences, reputational risk, access to capital — but if they haven’t felt the consequences of these risks first-hand, and they’ve been happy carrying on with business-as-usual until now, it can be a pretty hard sell.

The reality is that it’s incredibly difficult to sell vitamins, and almost effortless to sell painkillers. People don’t care about prevention: especially for negative outcomes they’ve never experienced before. Pre-COVID, only epidemiologists and Bill Gates cared about preventing a future pandemic. Post-COVID, everybody cared.

The second is far more insidious. It’s that we now see genuine moral failures — ecosystem collapse, natural disasters, child exploitation — as business risks, and not as the actual catastrophes they are.

What does it say about our world that we're more likely to get a board's attention by citing reputational risk rather than, say, the fate of human lives?

We’ve reached the point where risk is starting to sound like a perverted euphemism for human and environmental wellbeing. Oscar Wilde would have a field day with the way we’re hiding behind these sensible-sounding weasel words that all lead back to one place: the money.

Stop child labor? Sure, if it means it’s no longer profitable for us to do so.

Reduce our carbon emissions? Sure, if there’s a price on it.

Update our procurement policy? Sure, if it reassures our investors.

Even the way we define sustainability in the corporate world reflects this gross insistence on profit. Take this line I lifted from the FSA/SASB Credential Study Guide (something

and I are working toward in our “spare time”):Companies and investors have come to a shared realization that financial returns can be sustained only if companies are well governed and the social and environmental assets underlying those returns are not depleted.

I get it, and I agree, but also — ew? What are we — and what are the trees? Simply capital assets ready to be turned into a profit?

I’m grossed out now, so I’ll probably wrap this up.

I don’t have a crazy solution; just a simple one.

Let’s just start talking about sustainability and ESG again in the way CSR campaigns used to. Let’s talk about it as mattering for its own sake, and not simply because it may cause a blip in shareholder profits ten years from now.

Let’s talk about why trees matter and why human lives are special.

Let’s talk less about the bottom line and more about life outside the boardroom.

That’s where most of what matters happens, anyway.

Even the icon of good corporate neighborliness, Patagonia, has not achieved sustainability. Do even use the words "corporate sustainability" is a tail. One of complete disingenuousness or an impressive lack of understanding.

Love love love this. Feel like we've lost the heart of what sustainability is about. Keeping alive the earth we all love!!!!