TCC #53: Is AI ethical?

On ecology, + hot takes from the world's 100 largest companies

If you’ve been following along here, you know that Amelia and I recently analyzed the sustainability reports of the world’s top 100 companies by market cap. We observed that reports are more detailed and contain more data than ever, yet often fail to communicate the bigger picture effectively.

One thing that caught our attention is how companies are communicating around their use of artificial intelligence (AI). In this year’s reports, AI truly stepped into the spotlight.

Some companies chose to highlight AI’s role in driving climate action. Amazon, for instance, is using AI to ‘optimize packaging types.’ International Holding Company is using AI to ‘proactively identify potential faults in energy infrastructure.’ And Meta, in collaboration with World Resources Institute (WRI), used its AI to launch an open source map of global tree canopy height in hopes that the data can ultimately ‘be applied to forest biomass and carbon stock monitoring.’

Others, like Cisco and Verizon, emphasized responsible AI principles, focusing on ethics, fairness, and mitigating risks like bias and privacy concerns. Apple, despite rolling out its ‘Apple Intelligence’ in 2024, doesn’t even mention AI.

Very few companies addressed how the use of AI impacts supply chain emissions or how they plan to manage the increased demand on energy resources. This is an interesting choice considering AI’s explosive growth and the fact that generative AI’s architecture is orders of magnitude more energy-expensive than task-specific systems.

According to this report from Goldman Sachs, a single ChatGPT query requires ten times the energy it takes to power a Google search.

In light of it all, we can’t help but wonder — is AI bridging gaps or making new ones?

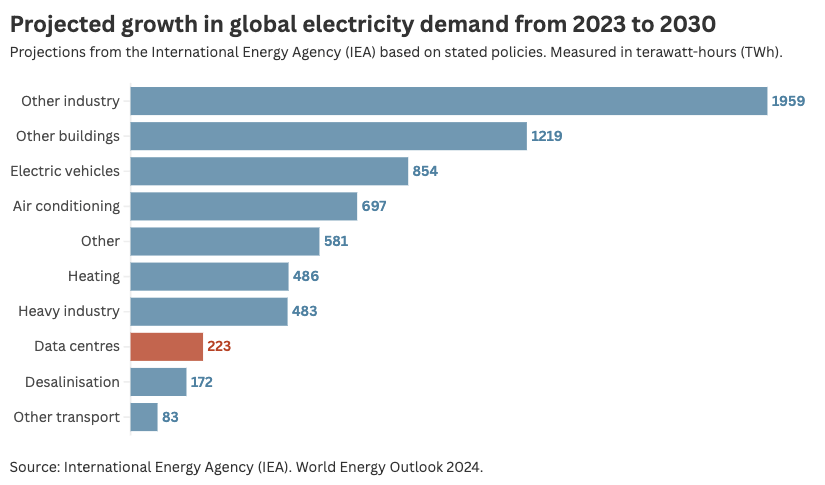

When I sat down to write this, I assumed I’d be horrified by what I found. Then I stumbled upon this article from Sustainability by numbers. The IEA, in its World Energy Outlook 2024 report, projected that data centers would account for only 3% of electricity demand growth from 2023 to 2030.

Given the headlines and hype around AI and energy use, this was surprising to me. It put things into perspective. Makes me think of the guilt people are made to feel for a ‘carbon-heavy’ website, while the bad actors of the world are rallying people behind one simple and incredibly damaging phrase: “DRILL, BABY, DRILL.”

That said, given the crisis we’re in, skyrocketing emissions from the world’s biggest tech companies — largely due to increased use of AI — is nothing to sniff at.

Google’s 2024 Environmental Report revealed that its emissions increased by 48% since 2019, a surge attributed to its data center energy consumption and supply chain emissions. Since 2020, Microsoft’s emissions have grown by 29%. The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) recently delisted Microsoft, a company long applauded for its climate leadership, for failing to meet emissions reduction targets. OpenAI doesn’t even disclose its emissions.

This is clearly a problem that needs to be addressed. Microsoft, to its credit, is investing heavily in carbon removal to offset its soaring data center emissions. More tech giants will need to follow suit.

But if I take a step back, I’m more concerned about the ecology (the presence of interrelationships: the unbreakable cords that tie everything to everything else) in which this tool is being built — and whether that ecology, and more importantly, our human view of it, is capable of nurturing a tool that will make the world a better, not a worse, place.

Late last year I read a fantastic book from James Bridle.

One key question posed by the author is, “How can we change ourselves, our technologies, our societies, and our politics to live better and more equitably with one another and the nonhuman world?”

The author writes (and I agree) that in Western society, we have a very limited definition and understanding of what ‘intelligence’ is. We tend to view it as ‘what humans do.’ James Bridle tells us that this definition has played a profound role in shaping technology and how we use it.

We already know that AI has biases — it exhibits political bias and tends to skew toward American norms and values.

“All the different ways we’ve tried to build AI over the years have always been shaped by that definition of human intelligence. And increasingly that’s looked damaging and dangerous.”

I often think about how technology is pushed on all of us, whether we want it or not. Such is capitalism. These tools, particularly AI — which is so culturally significant (so many of us are so endlessly fascinated by it) — are developed to mirror ‘human intelligence’ as it is perceived and dictated by the rich and powerful men responsible for its proliferation. I worry that when intelligence is defined and controlled by such a narrow set of actors, we risk building tools that reinforce their worldview rather than expanding our own. As AI increasingly mediates how we engage with the world, we may find ourselves further removed from reality — not just in how we think about technology, but in how we think about everything.

“The moment the real world is completely abstracted into the universal machine is when we lose our ability to care for it.

All computers are simulators. They contain abstract models of aspects of the world, which we set in motion — and then immediately forget that they’re models. We take them for the world itself. The same is true of our own consciousness, our own umwelt. We mistake our immediate perceptions for the world-as-it-is — but really, our conscious awareness is a moment-by-moment model, a constant process of re-appraisal and re-integration with the world as it presents itself to us. In this way, our internal model of the world, our consciousness, shapes the world in the same way and just as powerfully as any computer.”

A living creature is shaped by the environment in which it’s nurtured. The same is true for the tools we build. We have to assume that AI, built in our capitalistic and extractionistic society, is designed to cater to more of the same. To keep society on its current trajectory — a trajectory that caters to the status quo.

We absolutely need to worry about AI and its growing hunger for energy. But more so, we need to think about how we can make machines, and encourage ‘intelligence,’ that is better suited to the world we want to live in. To a society that operates within our planetary boundaries. One that is fair, and equitable.

“The question, then, is what are the characteristics of models — and thus of machines — that make better worlds?”

This conversation is so much bigger than my ability to tie it neatly into a discussion about corporate sustainability reports. I think my point is that sometimes, as sustainability professionals, our focus is misguided.

But I’ll leave you with this. Right now, much of the messaging around AI in corporate sustainability disclosures — and everywhere else (!!) — feels unbalanced.

Many companies emphasize AI’s potential to ‘drive efficiencies’ — yet very few acknowledge its real and growing impact on emissions. This gap in disclosure mirrors a broader problem: a failure to fully reckon with AI as both a tool and a force that shapes the world according to the systems and structures that built it.

Companies are treating AI as a sustainability solution rather than a sustainability problem. In reality, it’s both.

Google and Microsoft are outliers in publicly acknowledging their AI-driven emissions growth. We need industry-wide accountability.

Sustainability reporting has always been about narrative control. Companies want to tell a story that makes them look good. But the AI story is too big, too messy, and too consequential to be told only in part.

Disclosing numbers, in itself, is not an act of transparency. In fact, it can be quite the opposite. Data dumping is one way to make it harder for general readers to understand what’s actually going on and whether companies are making genuine progress toward their goals.

True transparency requires asking the hard questions and acknowledging contradictions. If we look deeper, what’s more important than AI’s contribution to rising emissions (which it turns out is actually quite small in context) — is ensuring that the systems and tools we build are serving the future we claim to be working toward.